I just played my first game of The King’s Dilemma, which is the most fun I’ve had playing a board game in a long time (and that’s speaking as someone who plays somewhere between fifty and a hundred board games every year).

This man is suffering, but not from success.

In the King’s Dilemma, each player takes on the leader of one of the king’s noble houses: you are the real leaders of the kingdom standing behind the figurehead king. The entire game is about reading cards from a deck that present you, the king’s council, with questions and resolutions to vote on (with various consequences, negative or positive). The things you do affect the kingdom’s military strength, economy, health, morale, and knowledge.

A merchant sold spoiled food to your citizens. Do you punish the man and make an example of him? If you do, it will discourage anyone who might try to do the same (improving the health of your kingdom), but it might also have a chilling effect on trade (worsening the economy). Punishment or no? Aye or nay?

You’ve discovered a rare metal that might be useful for forging weapons. Will you use it to bolster your own military, or seek economic benefits through trading the new metal to neighboring nations?

Each card has printed icons showing some of the immediate consequences, but once you flip the card over and read the prose describing the aftermath of your decision, you’ll often discover that there may be hidden consequences that might have only been vaguely hinted at by the front half of the dilemma card. (This is the part where the game tells you to “open envelope #46, read the story card, then add the rest of the cards from the envelope to the dilemma deck and shuffle it.”) When voting on a resolution, you can never be completely sure what the second-order effects of that decision will be, and the full consequences of that decision might not be seen until a generation or more later. (This is a legacy game: at the end of each session, the deck of dilemma cards is placed back into the box to be revisited next game, when each player around the table takes on the role of the next descendent in their noble house’s lineage.)

Every member of the council can commit any number of power tokens from their supply to either an “Aye” or “nay” vote…or take the third option, and abstain. (Because you stayed home to attend to your house’s affairs instead of attending the vote, choosing to abstain from the vote allows you to accrue a bit of power which you can use for future votes, as well as money, which can’t vote directly, but might be used to bribe other players in future votes.) In addition to the direct consequences of your actions, new story cards will be added to the deck, presenting you with branching consequences for whichever path the council decided would be best.

However, what’s good for the kingdom may or may not be what is best for your particular noble house. The game begins with everyone secretly drafting a “hidden agenda” secret card which defines their own scoring conditions.

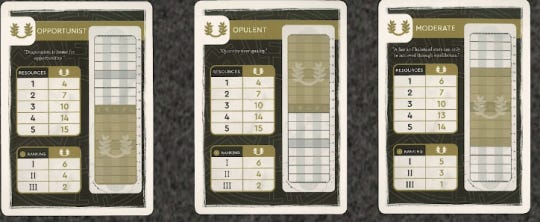

Sometimes your “hidden agenda” will oppose someone else’s: for example, the opportunist (who wants the kingdom to be weak) is directly at odds with the person who desires opulence (and wants the kingdom to be strong along every metric). However, more often than not, your goals are conditionally aligned with other players: the moderate player wants all of the tracks to be close to the middle, which means that they’ll want to strengthen military efforts if the nation’s borders are looking weak, but they’ll start to do the opposite if the nation’s military starts getting too strong.

This conditional overlap of hidden victory conditions leads to naturally shifting of alliances throughout the game in a way that’s completely organic, which also leads to great moments of drama and betrayal when the person who you cooperated with on the last three votes agrees to help you with another vote, only to reverse course at the last minute. (Of course, you knew that eventually, your interests would diverge, something that you will surely bear in mind as you curse your former friend’s sudden yet inevitable betrayal.)

This set of hidden incentives is what undergirds every vote in the game: everyone’s route to victory looks different, and it may or may not coincide with a prosperous kingdom.

The King’s Dilemma is a game that encourages light roleplaying. A big part of the fun comes from the fact that you begin the campaign by choosing to represent one of twelve unique noble houses, and a lot of the fun happens from picking a house with a philosophy that you get to embody, with each house having a tagline like “Never Break a Deal” (the motto of the merchant house) or “Tranquility In Death” (the house that takes on the unenviable task of defending the southern border, and seems to enjoy war and conflict just a bit too much). It’s exactly the kind of thing that appeals to the sorts of YouTube shows that are “friends sitting around a table, dressed in medieval costumes and playing larger than life characters.”

Funhaus, true to their channel name, clearly had fun with this one.

But the game is also about roleplaying in a different way: there’s a real sense that, within the fiction of the universe that the game inhabits, every single debate that takes place is kind of a LARP, a sort of in-universe play-acting. The king’s council members may all claim that they want what’s best for the kingdom, but what they say may be a put-on for the sake of advancing their own hidden agenda.

For example, on the final dilemma of the night, we were presented with the question of whether we should raise taxes on the prosperous and flourishing metalworkers guild for the purpose of feeding the poor. (Being that it was the final vote of the night as our aging was in his twilight years, any second-order effects of raising taxes would likely end up being a problem for the next generation to deal with.)

As the first person to vote, I began with an impassioned speech about how as the nobles who had been tasked with stewardship of the kingdom, it was our responsibility to ensure that all people in the kingdom benefitted from the kingdom’s newfound prosperity, and that passing the tariff would be the best way to ensure this.

However, my true reasons for trying to persuade the table of an “aye” vote were far more cynical: it’s true that I wanted the “health” track to stay high, but this was largely because I had a objective token that meant that my house would be blamed (and thus lose prestige) if the kingdom’s food supply got too low. If we didn’t come up with an immediate short-term solution to the current hunger crisis, my house would lose 3 prestige points! And so my character, within the fiction of this world, LARPed as someone who was concerned with the welfare of the people, when in fact he was only concerned with the image of his noble house. How do I know that my character was only cynically LARPing as someone who cared about charity? Because as soon as someone at the table offered me 12 gold to change my vote, I immediately accepted the offer.

It was one of those perfect moments of ludonarrative harmony, where the game’s mechanics perfectly convey the game’s themes and story. What better way to tell a story about cynical, self-interested, backstabbing aristocrats who treat politics as nothing more than an exercise in gamesmanship than by presenting us with a set of game mechanics that would guide us to act out those exact scenarios ourselves?

The game was full of moments like this, where the theme just sang. And what’s best is that these moments will happen even if you don’t go out of your way to “lean into the fun.” This isn’t a game where you have to choose between doing the “fun” thing instead of doing the thing that will make you win: the game’s mechanics are structured such that the best moments emerge as a result of everyone at the table ruthlessly pursuing whatever tack will result in them having the largest share of victory points at the end of the game.

Every moment is about doing the thing that will benefit you most, all the while trying to persuade everyone at the table that what you’re doing will actually be beneficial for them, and they should totally support you in the resolution that you’re trying to pass (or block)…while also hinting that, while you are definitely defending your position out of principle, you’re not so principled that you couldn’t be persuaded to change positions if they made the right offer.

The game continues until the king abdicates or – if the council governs well – until enough years have passed that the king dies of old age. Our king lived long enough to die in his bed, surrounded by his loved ones (and us, his council of scheming advisors). And as I proved more successful in scheming and earning prestige than anyone else at the table, I get to name the king’s heir, who will take the throne for next week’s game. I won tonight’s game, but the campaign has just begun. The king is dead, long live the king.