[This post discusses the ending of several movies, including Baby Driver, Monsters University, and Rocky.]

Movie protagonists are often breaking the rules. This is true even when our protagonists are on the right side of the law: nobody’s perfect. (And if they were, we probably wouldn’t like them as much: it’s hard for a character to have a “growth arc” if they start from a place of perfection. Making occasional mistakes reminds us that, just like us, they’re only human, making them more relatable.)

But when our protagonists break the rules, it often leads toward one of two different endings: either they get caught and punished for their transgressions (which can make for a feel-bad ending), or they get away with it scot-free. Most movies opt for the latter, but it can often feel unsatisfying, because there’s a real sense in which we want to see our protagonists reap the consequences of their actions. We want to see people get what they deserve.

Usually, it’s not a problem for them to suffer the consequences if their transgression is minor. For example, if the main character says something mean to his love interest, he can get a slap in the face – and having paid the due penance for his transgressions, he can then immediately be rewarded with whatever feel-good conclusion the audience is in the mood for.

However, sometimes the protagonist’s transgressions are more dire, and demand more dire consequences. Recently, I’ve found two movies that manage to end with something that is, in an objective sense, a very bad outcome for the main characters, and exactly in proportion to what they deserve for their significant transgressions during the film, yet still allows for a “feel-good” ending.

Heist movies are the classic example of a movie formula where the protagonists break a ton of rules and, in the case of a feel-good ending, basically can’t suffer any real legal consequences. Either they get caught and it’s a moral aesop about how crime doesn’t pay, or they get away with it and we’re happy that our characters, who are really quite morally virtuous apart from their tendency to commit acts of robbery, are able to enjoy the spoils they’ve absconded with.

Baby Driver is a movie that strikes an incredible balance. In the end, our main character Baby doesn’t get away with his crimes. He’s committed a lot of crimes, and been involved in a lot of robberies. And not the non-violent kind, either!

At the same time, Baby was always “one of the good ones.” He was never the guy who held the gun; he was always the one behind the wheel. In fact, for basically his entire criminal career, he was blackmailed into it. Of course, the lazy method would be for the judge to have pity on him – he was forced to commit crimes! But that would be ignoring the fact that the entire reason he got blackmailed in the first place is that he happened to steal a car from a criminal kingpin – Baby was boosting cars well before a villain put a gun to his head and forced him to do it.

But as we see Baby marched to his prison cell, it’s intercut with testimony during his trial. Everything that we could have said in Baby’s defense is articulated by witnesses speaking in his defense:

“He got himself into a bad spot. I was just trying to get him out. I believe the defendant is of good character. He didn’t deserve what happened to him.”

“It was the strangest thing. Before he drove off, he threw my purse right at me. Then he actually said ‘I’m sorry.’” (A delightful callback to a comedic moment earlier in the movie: Baby might resort to carjacking when he’s in a pinch, but he is the most polite carjacker you will ever meet. He doesn’t need your valuables; he just needs a getaway vehicle.)

“He made a mistake when he was younger, and it’s haunted him ever since. When he tried to get out, he was pressured even harder. It was never his fault. He’s got a good heart. Always has. Always will.”

Maybe it’s the fact that Sky Ferreira’s cover of Lionel Richie’s Easy Like Sunday Morning is the musical bed for this scene, but there’s something about the sequence that feels incredibly cathartic. Baby Driver might be our protagonist, but he’s not innocent in all of this. His actions have consequences, and he gets sentenced to prison time for them.

At the same time, we’re left with the distinct impression that he has a life waiting for him on the outside. At the very least, Deborah is there waiting for him.

We can rest assured that Baby has no desire to return to a life of crime – he and Deborah will be content with a modest life together. Indeed, a “modest life” is never something that either of them would need to settle for. Having a quiet simple life has been their aspiration for as long as they’ve known each other. Baby ends the movie knowing that he has years of prison time ahead of him, but also knowing that he’s on the start of a path to redemption. It’s enough to put a skip in his step as he walks across the prison yard. (Well, maybe not a literal skip in his step, but at the very least, it’s written on his face: he feels good about the path he’s on.)

Baby Driver came out in 2017, but I’ve already lost count of how many times I’ve watched it. I think the ending is a big part of what keeps me coming back to it. I love this ending – there’s really nothing like the catharsis of seeing Baby held to account for his actions, while also having his virtues acknowledged. Those virtues might not be enough for him to avoid all punishment, but in a way, his virtue its its own reward. It’s a heist movie that ends with the main character getting caught and spending years behind bars, and yet it’s an incredibly feel-good ending that just leaves you satisfied for all the right reasons. (After all, we’ve seen the fate of Baby’s confederates: we know that he could have encountered fates much worse than prison.) There’s really nothing like it.

Well, almost nothing. Last night I finally got around to watching Monsters University.

It’s a fun movie – the central plot is the classic “underdog sports story.” Mike Wazowski has no talent for scaring – according to the bigshot jock voiced by Nathan Fillion, the only way someone like Mike could end up working at a place like Monsters Inc is in the mailroom. Of course, because this is a prequel, we know that Mike’s story ends with him and Sulley being best buds together working at the Monsters Inc scream factory as professional scarers, so the odds can’t be that stacked against them, right? After all, the stakes are too high for them to fail: besides the fact that they need to be ready for the events of Monsters Inc, Mike is able to parley for a chance to get into the university’s scare program only because he makes an agreement with the Dean that if he fails, he’ll leave the school. With stakes that high, it seems only inevitable that Mike and Sulley will fulfill the classic underdog trope and lead a team of lovable losers to victory through sheer force of will (and the power of friendship).

Except, as we find out, force of will and the power of friendship aren’t enough to win you the big game when the thing you’re being tested on is talent and athleticism. Mike gets to experience the triumph of victory…but quickly learns that it only happened because Sulley cheated.

Mike and Sulley both bit off more than they could chew, and made a number of poor choices along the way. Sulley, unable to accept loss, cheated to achieve victory. Mike, unable to cope with experiencing loss, breaks into the university’s door department to mope around in the human world – which is strictly verboten and extremely dangerous.

But…in the course of solving the problem that they’ve created themselves (combining their efforts to escape the human world by using scare techniques the likes of which have never been seen before), we learn that Mike and Sulley do have what it takes. The Dean recognizes it, too. It almost feels like she’s about to offer them leniency. After all, this is a prequel movie: we know that all of this has to end with Mike and Sulley working at Monsters Inc in the scare department, right? That means the Dean has to let them back into the university’s scare program! Surely their acts of daring and bravery show they have what it takes to make it in the Monsters University scare program!

And so it comes as no surprise when, at the end of the third act, the Dean comes out just as they’re about to depart. We see what looks like a smile on her face for the first time in the movie.

Except, of course, it would be crazy if they got off scot-free. Mike broke into the human world, which is about the worst possible thing a monster can do. And if the cheating scandal weren’t enough to sink Sulley, there’s also the fact that he followed Mike into the human world (his intentions were noble as he wanted to save his friend, but still extremely dangerous and just as verboten).

The Dean has nothing but kind things to say to them. But that doesn’t mean she’s going to rescue them from the consequences of their actions.

The two get no leniency. We feel an odd mixture of elation and defeat. On one hand, they got the validation that they craved: the Dean, who thought it was impossible for Mike Wazowski to ever be a scarer, now admits that she may have misjudged him. On the other hand, their lives are ruined. They must now reap what they have sown. What will become of their dreams now? And maybe more importantly, how the heck are we supposed to get from here to the events of the original movie that takes place several years later in the Monsters Inc chronology?

And then, Mike remembers something.

“You know, there is still one way we can work at a scare company. They’re always hiring in the mail room.”

Mike and Sulley start at the absolute bottom rung of the corporate ladder. But there are worse fates than doing blue collar work. After all, the entire theme of the underdog sports story that got us to this point was to show that Mike (and, with Mike’s encouragement, also Sulley) are the kind of monsters who will do whatever it takes to achieve their dreams, simply willing it to happen through sheer enthusiasm and force of will and, of course, the power of friendship. After all, anything can be fun when you’re doing it with your friends. As Sulley says, “This is better than I ever imagined!” They approach the job with an enthusiasm that tells us that they’re on their way up within this company.

The rest of their journey is shown to us in montage:

They’ve got that ambition, baby. This week they’re mopping floors, next week it’s the fries:

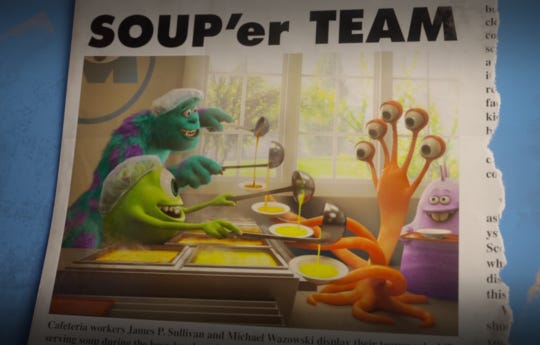

Of course, it’s only a matter of time before the company holds “try-outs” for the scare team, and from there, the rest is history. Plus, if the original movie is fresh enough in your mind, you’ll appreciate the easter egg references to the girlfriend that Mike met during this time (and the constant beratement he constantly got over needing to file his paperwork):

Over the course of the movie, they made some good decisions – mostly the ones relating to the power of friendship and hard work. They also made some bad decisions – mostly relating to playing fast-and-loose with the rules of their institution. Their college careers come to an unceremonious end.

And yet, even though the movie ends with them getting kicked out of college and spending “the best years of their lives” working blue collar jobs, it feels like an undeniably happy ending for the two of them. They reap exactly what they sow – for worse, and for better. They don’t get to hide from the consequences of their actions…but that doesn’t mean things have to end on a dour note.

There’s something I really dig about that. It feels exactly like the first Rocky movie: Rocky is an athlete who trained and tried and fought as hard as he could – and still lost. And yet, though he lost the big boxing match, there’s dignity in his loss. And in the end, he succeeded at the thing that really mattered.

In all three of these movies, it feels as though we as the audience are being set up for a specific happy ending. Of course Baby Driver has to end with the getaway driver getting away. Of course Monsters University has to end with Mike and Sulley graduating from the scare program. Of course Rocky has to end with our main character winning the big climactic boxing match. But in the end, we don’t get these “obvious” endings, because getting them wouldn’t really be a reflection of everything that led up to that point. But we don’t walk away disappointed, because we somehow get something better. These characters may not get the “obvious” reward. They didn’t get what they thought they wanted. They didn’t get what we as the audience were expecting. But they get the things that really matter. And in a way, that feels even better.