In the “Santa debates” that take place in parenting circles, there are two major factions represented.

In one camp, you have the Santa deniers, who believe that it’s bad to deliberately teach children things that are untrue, and that one of the duties of a parent is to help their child construct a correct model of the world (or at the very least, a useful model).

In the opposing camp are the Santa enjoyers, who believe that teaching kids to believe in Santa fills their childhood with more whimsy and wonder. Santa enjoyers engage in rituals like leaving cookies out for Santa, and label the presents under the tree as gifts “from Santa” (as opposed to giving the parents credit for providing the presents and eating the cookies).

Some engage in even more elaborate rituals to create “evidence” of Santa’s nocturnal visit, and purchase stencils to create snowy-looking footprints leading from the chimney where Santa allegedly entered.

I am in favor of both truth and whimsy. I like being correct, but I also appreciate the power of imagination, and stories of the impossible. For me, it is not difficult for me to reconcile these.

Children, for their part, also seem to be pretty good at indulging in the joy of simulations (“play”) with the understanding that the rules of their “play world” operate differently from reality. They know that their toys can’t talk; that’s why kids need to use their own mouths to verbalize the toys’ thoughts and speech. The kids’ enjoyment of their toys seems to be largely undiminished by this. (Indeed, a big part of the appeal of “self-directed play” is that the kid gets to call all the shots: if the toys suddenly sprung to life and started moving and talking of their own volition, they would be wresting control of the narrative away from the kid!)

Kayfabe

“Kayfabe” is a term of art in the world of professional wrestling (or more broadly, worked wrestling) of the sort you’ll see on WWE, describing the “fictional reality” in which the characters partake in competition. This sort of wrestling “isn’t real” in the sense that it’s not an actual sports competition; the fights are scripted and the results are known in advance to the participants.

“Wrestling isn’t real” is not a particularly insightful observation, and it could only be mistaken for insight by someone who has never watched one of these fights: the audience, for their part, understand that Mark William Calaway is not capable of teleportation, nor can he control lightning and darkness. When audiences see The Undertaker get sealed into a casket, and then get vanished by a flash of lightning before his supernatural “resurrection from the dead,” they understand that they are witnessing theater, not a live sporting event that is intended to crown the best athlete.

And yet, despite knowing that “wrestling isn’t real,” audiences act as if it is: when the villainous heel steps onto the stage, they boo and hurl insults, as if he were a real person, and not an actor portraying a fictional character.

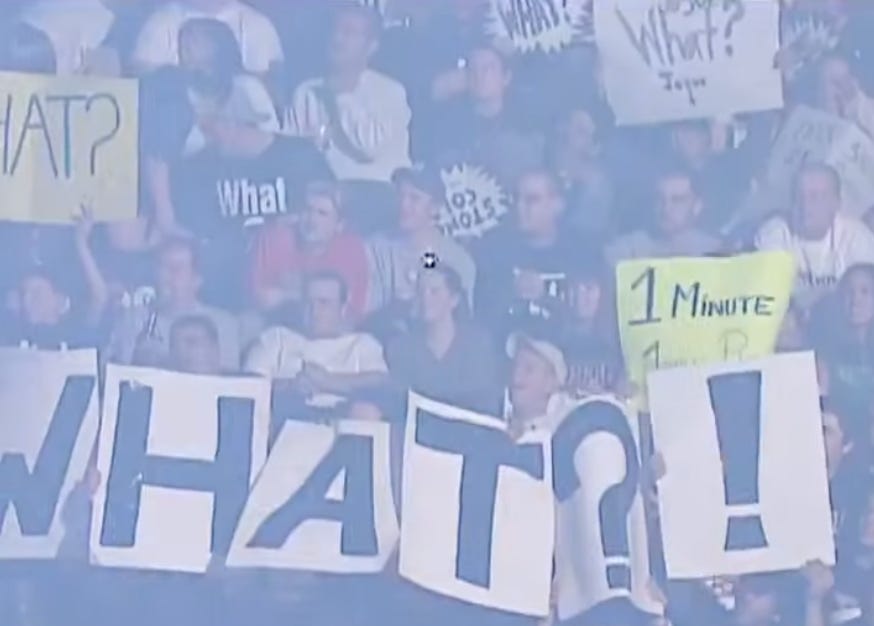

The audience gets to participate in various rituals: when Ric Flair delivers a chest chop, the crowd can yell “WOO!” in sync with the wrestler. When Stone Cold Steve Austin delivers his lines with a rhythmic cadence, each of his theatrical pauses can be filled by thousands of fans collectively yelling “WHAT?”

Audiences know they are participating in fiction. Or, at least, most of them do. But WWE’s audience is large and diverse, and it includes children who may not be worldly enough to understand that The Undertaker is a fictional stage character and that they do not actually cohabitate reality with a man who possesses the power to control lightning and rise from the grave.

Is kids’ enjoyment of wrestling diminished by the discovery that they’re staged? Arguably, the opposite is true: being “in on the joke” allows fans to enjoy both the kayfabe and on the meta level that exists before the kayfabe.

In New Japan Pro Wrestling, Kenny Omega is a pretty villainous character. His offenses include sending his allies to interfere with matches, using weapons when refs weren’t looking, and worst of all, having a really bad attitude about it. It would be very bad to cheer someone as dastardly as Kenny Omega and root for his misdeeds to be rewarded with victory.

The audience is participating in the fiction of pro wrestling: we’re “supposed” to cheer for the faces and boo the heels, but we can still “break character” and cheer for the heel in the moments when the stage performer pulls of technically impressive physical feats on stage, because we can separate the villainous character from the stage performer who brings that character to life.

If one day my child asks me why I’m cheering Kenny Omega despite his villainous actions, am I supposed to indulge in the fiction where Kenny Omega is a real person, and invent some plausible reason for why I’m cheering for someone who is obviously “the bad guy?” Only insofar as my child understands that is what I’m doing.

I, for my part, intend to teach my children that the stage persona of Kenny Omega is a fictional character and that his villainous misdeeds only within the canon of the fictional universe that NJPW has created. (I also intend to teach them that professional wrestlers are not actually superhumans who are capable of doing things like controlling lightning.)

Let’s play

However, I also intend to participate in “play,” which often involves saying things that are not true, and which are known to be untrue. Our ability to distinguish fact from fiction does not quash our ability to spontaneously create fictional worlds collaboratively through the power of “yes and.”

When a child says, “Look at me, I’m hiding!” they are simultaneously stating that they wish to be perceived, and that they wish to be not perceived. These two statements are only in contradiction if we are unable to distinguish the meta level claim (“I want Daddy to see what I am doing”) from the fiction they want to indulge in (“I want to be hidden and invisible to anyone who comes looking for me.”)

Adults engage in this kind of simulation and spontaneous roleplay all the time. It is the basis of most banter, like one can see on podcast studio discussions between Deji and Dayo Adebola:

Deji: “If women go through menstruation…why don’t men go through womenstruation?”

Dayo: “I will have you assassinated.”

We understand that Deji is not really asking this question because he wants an answer: with his typical deadpan delivery, he is engaging in his usual routine of playing a simpleton philosopher for the sake of a joke. Dayo is also playing a character: he suggesting a fictional world where someone believes that having someone assassinated is an appropriate response to a stupid rhetorical question.

This is fun, and it can be fun because we know that it is fictional. If Deji truly believed that he were sitting in a podcast studio with a man who intended to have him killed, he probably wouldn’t be having a very good time! He would probably be reacting in fear, or getting ready to retaliate in self-defense if necessary. But he doesn’t react like someone who has been confronted with a violent threat. (And if he did, we would understand that he was doing so in the same way an improv performer does, accepting the invitation to participate in a fictional improvised world by pretending to fear assassination.)

By engaging in surface level banter or play where we are “fighting,” we also operate on a meta level where we strengthen our bonds through shared performance. This is most easily done with friends, because it’s built on a foundation of trust that allows us to know this isn’t real conflict.

Without the ability to distinguish between fiction and reality, we lose the banter. We lose any sort of playful antagonism, lest it be mistaken for real antagonism. We lose the ability to play.

I’d like my kids to be able to participate in “play-fighting.” But they can only engage in play-fighting if understand the difference between performative aggression and actual aggression. (Kids who fail to grasp the distinction are prone to two major failure modes: in one, they actually hurt others in contexts where this wasn’t intended. In another, they become fearful of normal healthy rough-and-tumble play.)

The world of socialization becomes richer when we understand play on both the direct level, and on the meta level where we're strengthening a bond through shared performance. When everyone understands the meta level, we can engage in simulated violence, or playfully insult each other, or say false things to each other, as part of that shared performance.

I want my kids to have lives that are full of joy and whimsy. I want them to play. I want them to be able to spontaneously create fictional worlds, and recognize when others are inviting them to join and indulge in a shared fiction. I want them to learn to engage in the willing suspension of disbelief. It’s fun to pretend that Santa exists. But you can’t pretend to believe in Santa if you actually believe in Santa!

Disclaimer:

I am currently childless (though I fully intend for this to be a temporary state of affairs). Any place above where I am speaking of “my kids,” I am speaking of a future hypothetical, and as parenting expert Helmuth von Moltke said, “No plan survives contact with the enemy.” I’ve also been reliably informed that having kids is a transformative experience.

I am writing this post mainly to serve as a piece of documentary evidence for myself, so that one day I can look back on the beliefs I had on December 25, 2024. To the future me who’s looking back and shaking his head: Merry Christmas.